by MICHAEL K. IWOLEIT

Among the Hindi writers of his generation Nirmal Verma probably had the closest affinity to Europe and European literature. Decades before exile and alienation became a standard topic of successful Anglo-Indian literature, Verma explored the situation of an Indian in Europe and incorporated techniques and influences of modern European literature into Hindi fiction. Some of his best stories are reflections of the state of Europe after World War II as seen by an outsider.

Among the Hindi writers of his generation Nirmal Verma probably had the closest affinity to Europe and European literature. Decades before exile and alienation became a standard topic of successful Anglo-Indian literature, Verma explored the situation of an Indian in Europe and incorporated techniques and influences of modern European literature into Hindi fiction. Some of his best stories are reflections of the state of Europe after World War II as seen by an outsider.

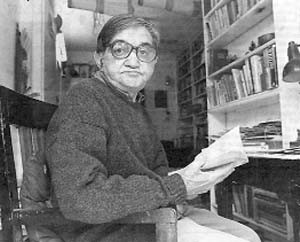

Born 1929 in Simla, he studied in New Delhi and in 1959 followed an invitation to the University of Prague where he lectured and translated Czech literature into Hindu, Milan Kundera among others. From 1968 he lived in London, traveled widely across Europe and wrote travel reports for the Times of India. In 1972 he returned to India and lived, interrupted by extended travels abroad, in New Delhi until his death in 2005. He published five novels, several essay collections, notes and travelogues and eight story collections. He is regarded as one of the founders of the Nayi Kahani, a new realistic narrative style in Indian literature of the nineteen fifties, and was repeatedly awarded with some of the most prestigious Indian literary prizes. His works have been translated into English, German, Italian, French and other European languages.

Vermas tales, most of them novelettes, some novellas, few short stories, offer little with regard to plot and events. Their focus is on what is only hinted at and remains unspoken between the characters. Many of his stories take place in memory. Defining experiences of hope, love and lost are only depicted in retrospect. Verma’s style is marked by a symbolic undercurrent that reflects the inner life of the characters in images of nature and landscape. Especially in his stories of the seventies he developed increasingly sophisticated means to explore the existential situation of his characters, abandoning any plot-based storytelling in favor of complex montages of moods, tensions and memories. Many of his tales are love stories but they are mostly stories of hopeless or unfulfilled love or love never admitted and thus characteristic of lives never fully lived, sometimes deteriorating into bleakness and passivity. In “Such a Big Yearning” an evening in a dance hall becomes a focus of several people who are all unable to express or fulfill their greatest desires. In „The Threshold“ young Jelly, so afraid of an empty and event-less life, fails to note that she has finally received the declaration of love she hoped for so long; the missed chance is formative for her whole life. In „The Gossamer“ the divorced Rooni hopes for a concession of her brother-in-law but he acts so indifferently that their affair a year ago seems almost unreal. The main character of „Fathers and Lovers“, just having returned to India, meets by chance his former lover and her little son and is reminded of a love that cannot be revived (in a twist of subtle irony that is typical of Verma, the other passengers in a tram mistake him for the boy’s father). The novella „Days of Longing“, set in Prague shortly after World War II, tells of a hopeless love affair that is burdened by the past from early on. Neither the main characters in “Here and Hereafter” nor in “The Man and the Girl” or „Weekend“ make any real efforts to turn their love into something lasting.

A number of Verma’s tales are about the emptiness and futility of a life after love or a loved one have been lost. In „The Migrant Birds“ the clumsy love-letter of a fatally ill admirer reminds teacher Latika, who works in a girl’s school shortly after the withdrawal of the British, of the only true love of her life and how she afterwards retreated into an existence devoid of any meaning. A visit to a small mountain town where they had spent some weekends in their youth makes the married couple in „The Hill Station“ aware of feelings that they lost and how their life is solely defined with regard to the past that will not return. In “Differences” a man visits his lover in a hospital where she recovers from an abortion. Although they talk about pursuing their relationship where they left it a year ago, both are already prepared to separate. This story, deceptively understated and event-less, is almost paradigmatic for Verma’s technique to leave the main conflict completely unspoken between the character who tend to circumvent any real resolution with gloom and self-deceit. Psychic degradation and a loss of emotions are also central to a number of Verma’s tales that depict the disintegration of family relations: The main character of „Last Summer“, who has just returned after several years in Europe, is again confronted with the lingering presence of his brother who serves in the army. As the estranged, the uprooted one he fails to find any base of communication with his father. „Maya Darpan“ is about the conflict between an older generation who lives only in the past and the young ones who try to find their own way out of despair and idleness. A masterpiece among these stories, and maybe Verma’s greatest story at all, is „The Dead and the Dying“: the prolonged and painful dying process of the father slowly reveals lifelong unstated and unresolved conflicts with his son who spends some days in his hospital room. In this complex and masterfully intensified story the surrounding area lends a tapestry of nature symbols – especially the jackals in the hills behind the hospital – to the psychological tensions between father and son. Here as in many others of Verma’s story nature gives voice to what the characters are unable to communicate.

Starting with the young Indian woman in „A Beginning“, who meets an English man on a passage to Ostende, a recurring character in Verma’s stories is the Indian immigrant who experiences the wounds inflicted on Europa by World War II from an outsider’s view. Europe appears in this story as a horror and a revelation likewise, thus striking a note for many of Verma’s later works. “One London Night”, one of the few action-centered stories Verma has written, depicts the situation of young immigrants in London who have fled racism and desperation in their home countries only to be confronted with a new kind of hopelessness in their adopted country. The uncertain position of an Indian who is always confronted with the question of returning to India – later a standard topic in Anglo-Indian fiction – is a subject of „Two Homes“ and several other of Verma’s stories. The return, if it takes place – as in „Last Summer“ or „Fathers and Lovers“ -, however, only deepens the character’s estrangement from his family and country. Verma’s characters are never rooted firmly, neither in love and relationships nor in family or ethnic ties. In essence his fiction is about alienation and loneliness, about the loss of any certainties, thus reflecting the personal experiences of a writer who has slipped into the peculiar transition area between two cultures.

There are, however, glimpses of hope in Verma’s stories. As a writer of shades and nuances he does not expect big, existential fulfillments but discovers small wonders of life only experienced by those sensitive and with an open mind. Among the unconventional young characters with courage for individuality that lend a certain optimism to his fiction, the most remarkable is maybe the adolescent girl in „The Lost Stream“ who observes life in a small alley from the roof of her parents’ house and listens to the noise of a hidden stream no-one else seems to hear. Even for those elder people in Verma’s stories – e.g. in “The Space in Between”, “The Morning Walk” or the masterly monologue “An Inch and a Half Above Ground” – who have retreated from life and quietly accept loss and decline, the withdrawal may turn out to be a kind of relief.

Copyright (c) 2017 by Michael K. Iwoleit

English translations:

An Inch and a Half Above Ground. Collected Stories, Rupa & Co., New Delhi 2004.

German translations:

Dunkle Geheimnisse. Erzählungen, Lotus Verlag Roland Beer, Berlin 2006.

Die Einsamkeit des Einsamen. Zwei Erzählungen, Lotus Verlag Roland Beer, Berlin 2006.

Traumwelten, Lotus Verlag Roland Beer, Berlin 1997.

Wolkenschatten. Frühe Erzählungen, Lotus Verlag Roland Beer, Berlin 2006.